On 14 May 2017, China’s president Xi Jinping hosted some 30 world leaders in Beijing at the first Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) Forum. He outlined plans to boost investment and trade in the Belt and Road economic corridors. More than 100 countries on five continents have signed up, showing the demand for global economic cooperation.

There were certainly questions asked when Victoria first signed a memorandum of understanding to join China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2018, but it wasn’t until the past week that the criticism reached a fever pitch.

The depth of the animosity over the deal shows the extent to which the BRI has become a faultline in the China-US competition.

And Australia, economically interdependent with China but a committed ally of the US, finds itself caught in the middle.

What is the BRI and what does China want?

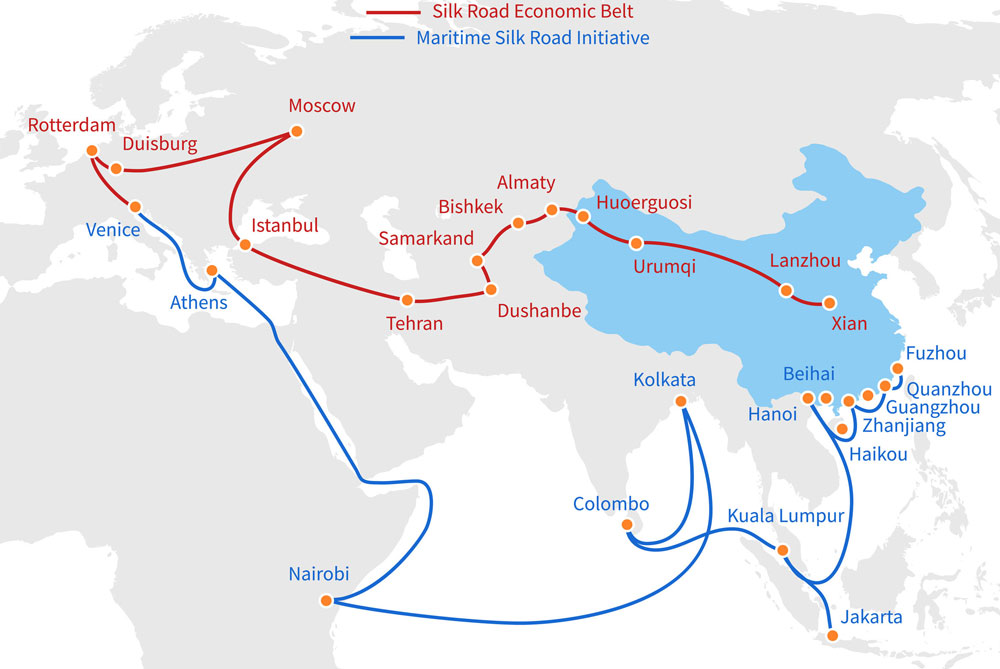

There is a diverse array of projects encompassed under the BRI umbrella, focused on six main “economic corridors”.

These corridors link China to Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe by land (the “Silk Road Economic Belt”), and to Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Pacific and east Africa by sea (the “Maritime Silk Road”).

To date, China has pledged an estimated US$1 trillion in investments in “hard” and “soft” infrastructure (from ports and high-speed rail to telecommunications and cyberspace) and signed memorandums of understanding with 138 countries.

The BRI is designed to help export China’s excess capacity by creating new markets for Chinese construction firms and capital goods makers. This should enhance domestic investment returns and stabilise GDP growth, in addition to spurring growth in underdeveloped regions. The project involves building roads, railways, pipelines and industrial corridors across some 67 countries, requiring significant tonnages of steel and cement, large numbers of workers, cranes and diggers, new dams, power stations and power grids. With over USD 3 trillion in international reserves (25%+ of the world’s total), China has enormous resources to support the success of the BRI.

What is the BRI and what does China want?

There is a diverse array of projects encompassed under the BRI umbrella, focused on six main “economic corridors”.

These corridors link China to Central Asia, the Middle East and Europe by land (the “Silk Road Economic Belt”), and to Southeast Asia, the Indian subcontinent, the Pacific and east Africa by sea (the “Maritime Silk Road”).

To date, China has pledged an estimated US$1 trillion in investments in “hard” and “soft” infrastructure (from ports and high-speed rail to telecommunications and cyberspace) and signed memorandums of understanding with 138 countries.

What are the benefits and pitfalls of BRI?

In thinking about BRI’s global and regional reception, we need to recognise there is demand for what Beijing is offering.

Its commitment of US$1 trillion is a drop in the bucket of the estimated US$26 trillion needed by Asia’s economies for infrastructure investment, but it still surpasses anything put up by other major regional players.

The “blue-dot network” announced by the US, Australia and Japan in November as a response to the BRI, for instance, was trumpeted as promoting infrastructure investment that is “open and inclusive, transparent, economically viable”.

But the initiative is not an infrastructure funding mechanism itself. Rather, it merely certifies projects that “demonstrate and uphold global infrastructure principles”.

While this might be an admirable goal, there is a problem, as former Asian Development Bank executive director Peter McCawley points out:

A road is a road, whether it is built with US or Chinese money. At present, it seems that the Chinese are prepared to fund the construction of infrastructure in Asia, while the US is not.

Concerns about the nature of Chinese investments under BRI are valid. Many BRI projects are financed through Chinese public financial institutions such as the Export-Import Bank of China that enjoy low borrowing costs and interest rates.

This enables them to lend on favourable terms to Chinese companies, who can then significantly undercut foreign companies for infrastructure bids.

Another concern is that Beijing is engaging in “debt trap diplomacy” by extending excessive credit to countries that will struggle to pay it back.

The aim is then to extract political and economic concessions or physical assets, such as ports or land deals, from those countries.

Several studies have suggested the “debt trap” narrative has been exaggerated. But while a Lowy Institute report last year noted that China has not “deliberately” engaged in debt-trap diplomacy, it added

the sheer scale of China’s lending and its lack of strong institutional mechanisms to protect the debt sustainability of borrowing countries poses clear risks.

Victoria’s BRI agreement: storm in a teacup?

Beyond the economics, the Belt and Road Initiative carries clear political risks for Australia.

Australia’s attempt to balance its alliance with the US and economic interdependence with China has become even more difficult, as both have become “rude and nasty” in pursuit of their interests under Donald Trump and Xi Jinping.

Some analysts claim Victoria’s BRI agreement means Chinese firms will be

building chunks of national infrastructure, perhaps with tie-ups to Chinese state banks and other entities.

But the reality may be more prosaic. The memorandum of understanding and subsequent “framework agreement” speak of mutual commitments to “promote practical cooperation” of Chinese firms in Victorian infrastructure and Victorian firms in “China and third-party markets”.

They are also not legally binding and may be terminated by mutual agreement.

Meanwhile, Premier Daniel Andrews said this week Victoria would not agree to telecommunications projects under the BRI, a key security concern.

BRI and the great power competition

The furore over Victoria’s agreement is due to the fact there is no Australian consensus on BRI or the broader issue of our relationship with Beijing. Debate on these issues is necessary if Australia is to chart a course between two great powers gearing up for confrontation.

Unfortunately, the debate on China has become toxic.

Those who recognise the risks of engaging with China, but still advocate for closer relations, are often lambasted as “craven” or worse. Those sounding the alarm bells about Beijing’s malign intentions are accused of sowing a “China panic”.

To say this is unhelpful is an understatement.

Some talk of a new Cold War between the US and China.

Yet, as the Cold War historian Odd Arne Westad, has noted, today’s China-US competition is not a replay of the past. The conflict between the two biggest powers will not lead to bipolarity, but rather

will make it easier for others to catch up, since there are no ideological compulsions, and economic advantage counts for so much more.

Tying ourselves ever more tightly to either protagonist is imprudent, as Westad says,

The more the US and China beat each other up, the more room for manoeuvre other powers will have.

Source: The Conversation

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!