Breathing Buildings, a leading provider of controlled natural and hybrid ventilation systems, has scooped the Commercial Ventilation Product of the Year Award at this year’s prestigious Energy Saving Awards. The company won the award for its new NVHRe, Natural Ventilation with Heat Recycling and Heat Recovery (NVHRe), which is its latest addition to its award-winning range of Natural Ventilation with Heat Recycling (NVHR®) systems. This is the second award Breathing Buildings has won for this innovative product, it also won ‘Commercial/ Industrial Ventilation Product of the Year’ category at the HVR Awards 2024 in September. Breathing Buildings was presented the accolade at a glittering awards ceremony at The De Vere Grand Connaught Rooms, London on 6th December 2024.

The Energy Saving Awards, organised by leading publications Plumbing, Heating & Air Movement News (PHAM News) and Energy in Buildings & Industry (EiBI), is an event celebrating the very best professionals, products and projects across the Plumbing, HVAC and Energy Management sectors. The awards have been created to acknowledge the important work that has been achieved by manufacturers, installers, contractors, suppliers and organisations to reduce carbon emissions and become more energy efficient. The standard of entries this year was exceptionally high and after a rigorous judging process Breathing Buildings won the award for its innovative NVHRe, which raises the bar on energy-efficient ventilation.

Marking the next step in hybrid ventilation technology, the key difference between Breathing Buildings’ original NVHR® range and the new innovative Natural Ventilation with Heat Recycling and Heat Recovery (NVHRe), is the addition of a low resistance heat exchanger cell within the unit. This allows the unit to benefit from both heat recycling and heat recovery, reclaiming even more heat than previous models, saving more energy, providing great occupant comfort, and allowing users to include it within the building energy assessments (SBEM).

Alexis Roberts, Brand Manager at Breathing Buildings said:

“We are delighted Breathing Buildings’ NVHRe won the ‘Commercial Ventilation Product of the Year’ category at the prestigious Energy Saving Awards 2024 and has been recognised by the industry. Our NVHRe takes all the benefits of energy-efficient hybrid ventilation one step further by providing natural ventilation with heat recycling and heat recovery. Providing an industry-leading ventilation product for commercial and public buildings, such as offices and schools. The Breathing Buildings NVHRe, boasts the lowest energy consumption and delivers 46% heat recovery efficiency with extremely low SFP levels to help building owners achieve their sustainability targets on the journey to Net-Zero Carbon. Breathing Buildings has completed the CIBSE TM65 methodology, these documents are readily available to help specifiers compare the NVHRe to other products in the market, enabling them to select the most efficient, sustainable products.”

Offering the lowest energy consumption for a hybrid heat recovery ventilation unit in the industry, the NVHRe combines 46% heat recovery efficiency with low Specific Fan Power (SFP) of 0.075 W/l/s to help maximise a building’s energy savings. In addition, the NVHRe has several different operating modes to minimise energy use, enhance indoor air quality (IAQ) and improve occupant comfort. An intelligent hybrid system, the unit automatically decides when and if mechanical operation is required, ensuring it only operates when absolutely necessary.

Providing excellent thermal comfort and enhanced IAQ, the NVHRe is designed to suit a diverse range of commercial and public buildings with high heat gains, such as schools, colleges, leisure centres, offices, theatres and even churches. The inclusion of the low resistant aluminium cross plate heat exchanger to the unit lowers energy costs by reducing the reliance on space heating to maintain thermal comfort in a room. It operates during colder external temperatures, typically below 7ºC when mixing recycled air alone is not enough to maintain the desired temperature for occupants.

The range also includes units that can be the primary source of heat; eliminating the need for other heating sources such as radiators, as well as a system that can offer further cooling. The British designed and manufactured units come in three models with product variations to suit every need with the standard NVHRe 1100 an NVHRe+ 1100 which includes a heating coil and is ideal for buildings in cooler areas; and an NVHRe C+ 1100 which features a heating and cooling coil for year-round comfort and full temperature control.

The NVHRe hybrid ventilation system’s ultra-efficient facade-based mixing ventilation allows single-sided, enhanced natural and hybrid ventilation in deep plan spaces whilst making the most of internal heat gains, with the addition of heat recovery to deliver superb thermal comfort and IAQ. Hybrid ventilation focuses on the vital balance of IAQ, thermal comfort, and efficiency by choosing the most appropriate mode of ventilation based on the internal and external conditions, allowing the NVHRe to be in the most energy-efficient mode possible at all stages.

Allowing low-energy hybrid natural ventilation, even in buildings with limited facade and roof space, highly efficient mixing fans mitigate cold draughts in winter and provide a ventilation boost in summer, with the addition of heat recovery to bolster winter thermal comfort, minimising the need for a primary source of heating for the space, such as radiators or air conditioning units, this reduces energy costs. Supplied with an external temperature sensor, and an internal temperature and CO2 sensor, as well as an intelligent controller the system monitors conditions to create an ideal indoor environment, boosting both productivity and wellbeing.

NVHRe optimises IAQ, comfort and efficiency by automatically switching between natural, hybrid and mechanical ventilation, maximising benefits. The unit has four modes: Summer Natural Mode, Summer Mechanical Mode, Winter Mode: Mixing and Winter Mode: Mixing with Heat Recovery. The Summer Natural Mode enables the unit to maximise the benefits of passive ventilation by opening the high-quality motorised damper and ventilating with zero cost. The Summer Mechanical Mode enables the hybrid technology to maximise ventilation by working in conjunction with other openings and providing cooler air. In Winter the Mixing Mode and Mixing with Heat Recovery strategies offer huge heating-bill savings as they recycle and recover heat while providing ventilation to ensure excellent IAQ and thermal comfort that enhance occupant comfort, health and productivity.

In addition, the NVHRe features a dedicated control panel seamlessly built into the side of the unit for easy access on-site, this is pre-configured. A micro-SD card is included free of charge, this collects operational data for up to 15 years. The data can easily be exported for analysis enabling the building owner to ensure the units are running efficiently.

Manufactured using high-quality components, the unit is easy to install and maintain. All core components are easily accessible by removing the panel beneath the unit. Each component can be serviced in-situ to ensure it operates efficiently and for as long as possible enhancing the overall longevity of the unit, rather than needing to replace a whole unit. In addition to incorporating the most energy efficient components and ensuring they are easily maintained. Breathing Buildings has given careful thought to the entire lifespan of the NVHRe, ensuring that all key components are recyclable at the end-of-use.

Breathing Buildings’ multi-award-winning natural ventilation with heat recycling (NVHR®) range has won a raft of awards. The company’s NVHRe won the ‘Commercial/ Industrial Ventilation Product of the Year’ category at the prestigious HVR Awards 2024. Meanwhile, its NVHR® range won the Energy Efficient Product of the Year Award at the prestigious Energy Awards, and also won three awards for providing ventilation to the East Anglian Air Ambulance project with the Breathing Buildings’ NVHR® range.

For further information on the Energy Saving Awards

For further information on NVHR®, NVHRe and E-stack ventilation,

as well as other products and services offered by Breathing Buildings

of call us on 01223 450 060

“Tai ar y Cyd represents a significant step forward in our commitment to building sustainable and affordable homes here in Wales.

“Tai ar y Cyd represents a significant step forward in our commitment to building sustainable and affordable homes here in Wales.

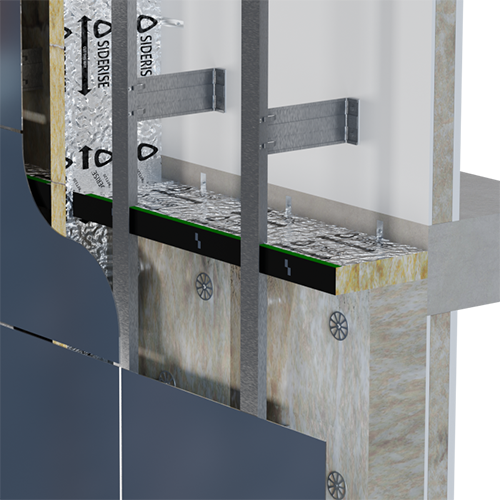

“Tai ar y Cyd represents a significant step forward in our commitment to building sustainable and affordable homes here in Wales. “Following the introduction of the Building Safety Act and particularly of Gateway 2 for higher-risk buildings (HRBs), we understand that specifiers— whether they are architects, fire engineers or contractors— must feel confident in the information they are using to make decisions and be able to access robust and assessed product data in the format they need. We have aligned getting the CCPI mark for our core products with developing a more holistic specification support package, including creating Specification Packs that summarise the relevant product information for the designated application, and building our partnership with the NBS.”

“Following the introduction of the Building Safety Act and particularly of Gateway 2 for higher-risk buildings (HRBs), we understand that specifiers— whether they are architects, fire engineers or contractors— must feel confident in the information they are using to make decisions and be able to access robust and assessed product data in the format they need. We have aligned getting the CCPI mark for our core products with developing a more holistic specification support package, including creating Specification Packs that summarise the relevant product information for the designated application, and building our partnership with the NBS.”