EJOT UK’s Mark Newell explains why the latest additions to its ETICS range are helping the EWI industry streamline its supply chain, and maintain consistently high quality during installation for the long-term benefit of specifiers and residents.

Like any assembled product, the performance of an EWI (external wall insulation) system or ETICS (external thermal insulation composite system) is only ever going to be as good as its component parts. A weak link in the system build-up will not only undermine its promise to improve the thermal performance of a property, but it could add complexity and hassle to the installation process resulting in additional time costs for contractors.

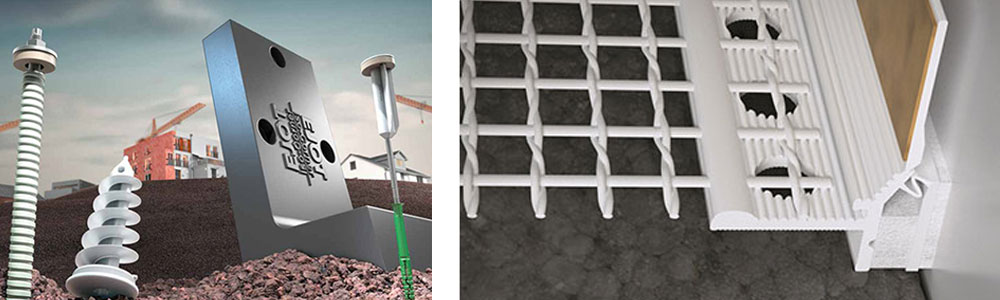

Advanced fixing solutions, therefore, have a crucial role to play, which is why EJOT has offered a range of innovative anchors – tube-washer and screw combinations – for many years. These are widely used throughout the UK’s EWI sector and specified by many of the leading systems providers. But the quality of the mechanical fixing for attaching insulation to the building substrate is just one of the factors contributing to efficient installation and performance of the completed system.

This has long been recognised by EJOT, which is why we have always offered similarly innovative and technically-superior ancillary products, such as fixing components that enable external elements including handrail and downpipe brackets to be mounted on the wall safely and securely.

The latest developments to this range, however, offer a holistic solution that could be a game-changer in terms of how EWI components are sourced. By extending the EJOT Pro-Line range of profiles, EWI system providers can now source their complete suite of fixing and attachment components from a single supplier. That brings a host of benefits as a number of systems companies are already realising, particularly in respect of improving quality consistency and making their systems easier for installers to work with.

Process optimisation and streamlined supply chain

For ETICS / EWI system providers, EJOT UK can effectively become a ‘one-stop shop’, which means they do not have to rely on different suppliers, often with their own payment terms and lead times, to complete their offer. All this means there is an immediate operational benefit in terms of the efficiency of ordering, delivery and invoicing processes, easing the pressure on staff resources for other purposes and reducing volumes of paperwork – all of which needs printing and generates waste.

The process optimisation possible through single-sourcing encompasses other environmental advantages too. EJOT can deliver the complete suite of EWI components and profiles on a single vehicle making one journey, which means there are fewer trucks delivering to a given site. This helps reduce the impact of site operations in local communities and enables the carbon footprint of the EWI supply chain to be minimised.

The EJOT ETICS range is also supported with an Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) to provide quantified data on its environmental impacts. This maximises transparency for specifiers and enables informed whole life cycle management decisions to be made when selecting systems for EWI or ETICS projects.

Helping installers achieve higher quality

EWI systems are already making a massive contribution to improving the energy efficiency of the UK’s ‘already built’ housing stock, but we have only just scratched the surface. Anything that can accelerate deployment of EWI, therefore, will enable more homes to be upgraded sooner rather than later.

One of the ways this can be achieved is to ensure installers are comprehensively supported to work more efficiently and achieve better quality consistency. This is a key consideration for every EJOT product, but it is particularly important where ETICS profiles and fixing components are concerned.

EJOT UK does this through a 360-degree service. This involves EJOT technical consultants providing on site services covering the three product segments – anchors, profiles and mounting elements – to ensure installers can achieve the optimum results.

For ETICS anchors, EJOT provides pull-out tests on-site and offers a digital product configurator to assist at the specification stage. The digital product configurator also supports the deployment of EJOT’s ETICS mounting elements, with additional support provided for pre-dimensioning, and, for profiles, its technical consultants carry out adhesive tests on-site – all with the aim of helping installers get the right result first time and deliver a quality installation for clients.

Improving performance of the system

By supporting installers, EJOT UK works to optimise the performance of the EWI system and ensure everyone in the supply chain maximises the benefits of its technically advanced products. All products in our ETICS range share the same high technical standards, but installation quality is key to ensuring they deliver on their promise.

Installed correctly, EJOT’s ETICS range reduces the risk of thermal bridging. This is a common issue for wall insulation systems which impacts on overall thermal performance and can result in dampness and mould growth on internal surfaces.

Thermal bridges can occur in many areas of the system’s construction, with anchors and edge profiles being particularly vulnerable points. Hence why EJOT’s R&D team has focused on creating products that address these risks, including through manufacturing all our profiles in PVC rather than aluminium and the development of a new patent pending PVC base ‘high load’ profile which features a hollow chamber design to reduce thermal transfer, while still maintaining high rigidity.

In addition, our profiles incorporate features to maximise quality throughout the EWI system’s lifetime. For example, Pro-Line profiles are designed to compensate for movement where applicable, such as around doors and windows, to prevent cracks developing over time.