What can go Wrong with Geothermal Projects?

Krafla Geothermal Power Plant in Iceland

How to explain the low energy output of one of the UK’s flagship geothermal projects?

In September last year, the UK Government announced a list of renewable energy projects that qualify for a minimum price guarantee for the energy delivered to the grid. Geothermal projects were among the winners for the first time, and the United Downs project in Cornwall, southwest England, was one of them.

However, the estimated energy offtake from United Downs looked a little meagre: only 2 MWe. Higher output can reasonably be expected for such a flagship and expensive project, where the producer well reaches more than 5,000 m and temperatures over 175°C are confirmed. What might be the cause for an energy output this low?

It is not only a low energy output; progress on constructing the site has also been much slower than anticipated. In June 2020, I listened to a talk by Ryan Law from Geothermal Engineering Limited, the project’s operator. At the time, electricity production was thought to be online in 2021. It is 2024 now, and there is still no electricity production, and the project’s narrative has moved significantly towards lithium production.

To learn more about what may have caused all this, GeoExPro spoke to Kevin Gray from Black Reiver Consulting, who has been working in the geothermal space for years and knows how to drill a geothermal project properly. Kevin is a real advocate for the geothermal industry, but at the same time, he does not shy away from being upfront about the risks of not sticking to a competent drilling strategy.

The United Downs project seems to be an example of a project where a competent drilling strategy was missing.

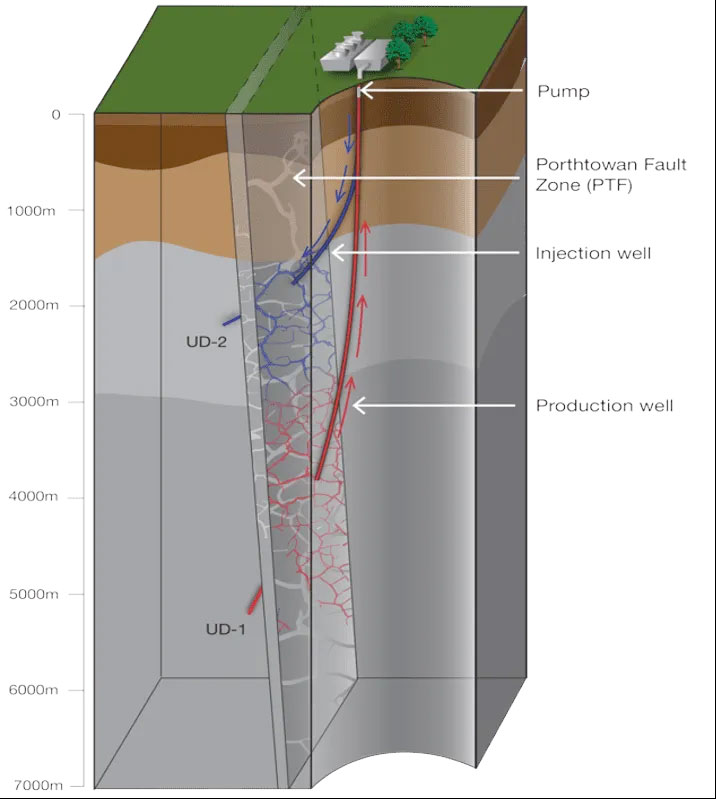

The United Downs project targeted a major fault zone in the granitic basement. Hot brines from a depth of around 4,100 m are supposed to be brought to the surface to power an electricity plant, with the cooled fluid subsequently re-injected at a depth of around 2,100 m into the same fault zone where it was produced from deeper down.

Schematic representation of the Porthtowan Fault zone drilled by the two United Downs geothermal wells. Source: Geothermal Engineering Limited

As virgin granite has no permeability, any fluid flow into the wellbore relies on natural fractures. Therefore, it is critical for high-profile projects of this kind to preserve the permeability as much as possible during the drilling process.

“This is easier said than done because penetrating a naturally fractured zone is often associated with mud losses while drilling and, therefore, the risk of clogging up the fracture space”, says Kevin. “And that is most likely the thing that went wrong here.”

“An explanation as to why the fracture space was clogged up so badly is the type of drill bit used”, continues Kevin. “The project went through 38 roller-cone bit runs, and guess what roller-cone bit cuttings do when drilling through a fracture zone? The cuttings can completely pack off your fractures, decreasing their capability to accommodate fluid flow.”

Kevin further explains that there are bits on the market that can do a much better job, as it is in this particular realm where a lot of innovation has been taking place over the last few years.

“On that basis, it looks likely that there was no proper assessment of the type of drill bit to be used”, Kevin concludes. “Sure, even with the best bits, it will always be a challenge to prevent any formation damage completely, but in this case, it seems that the low projected energy output can be directly related to the lack of a proper drilling strategy.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!