Prefab Taking Flight at U.S. Airports

Expansions and modernizations at airports can be logistically tricky. They often involve shutdowns and delays, adding to travel headaches and causing a loss of revenue. But prefabrication and modular construction are emerging trends for airports, promising benefits that include fewer disruptions, shorter project timelines, and safer work sites, according to advocates of the methodology.

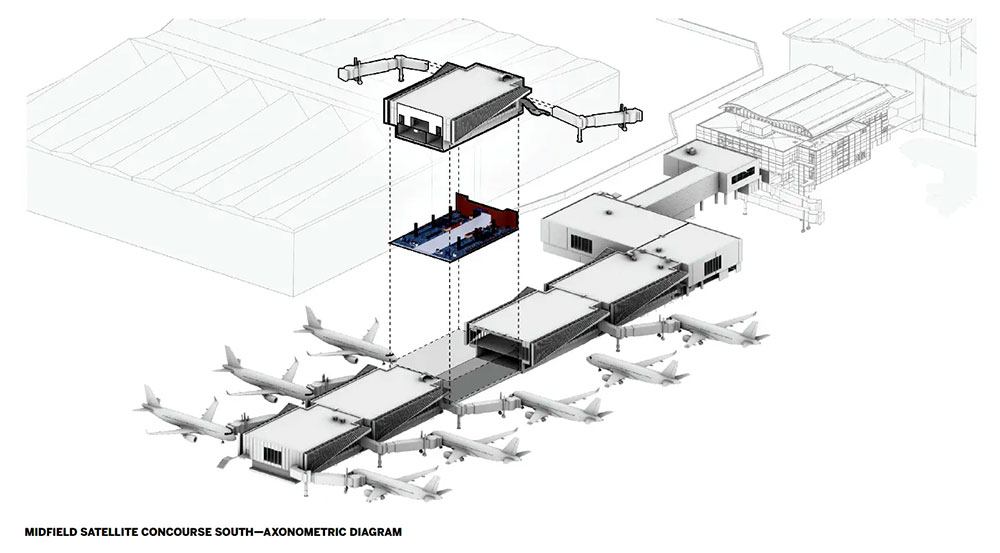

Current projects at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport (ATL), while not the first in the country to use remote construction, nevertheless illustrate the potential of different variations on the approach. LAX is extending its Midfield Satellite Concourse to the south, adding 146,000 square feet and eight gates for narrow-body aircraft in a process that design architect Woods Bagot calls off-site construction and relocation (OCR). In Atlanta, architects Corgan and Goode Van Slyke are relying on a hybrid of modular and traditional construction to expand ATL’s 44-year-old Concourse D by 75 percent to accommodate larger airplanes and more travelers.

In the case of LAX, workers built nine aluminum-clad, steel-framed segments, with a typical one measuring 63 by 138 feet, in an assembly yard just outside the airfield operations area. Then, over nine nights this past October, with runways temporarily closed, crews from heavy-lifting company Mammoet transported the roughly 1,000-ton modules the 1¾ miles to the building site on specialized multiwheeled vehicles known as self-propelled modular transporters (SPMTs).

Ian Lomas, the chair of Woods Bagot’s Los Angeles studio, says that the architecture of the new concourse is intentionally straightforward, but with proportions and geometry inspired by California Modernism. The modules do, however, have a feature that deviates from that era’s mostly rectilinear forms: an angled and subtly curving brise soleil. The shading device allows for daylighting and views without the need for other measures to mitigate heat gain and glare, such as coatings or electrochromic glazing. And “it creates a simple ripple across the facade,” says Lomas.

Structurally, each segment is its own building, laterally supported by a pair of moment-resisting frames in one direction and buckling-restrained braced frames in the other, explains Stuart Brumpton, project manager for Buro Happold, the expansion’s structural engineer, as well as its sustainability, lighting, and acoustical consultant. The design takes into account the potential for intense seismic activity in the earthquake-prone region, but it also prevented damage of nonstructural components during the modules’ transport, since their cladding, glazing, m/e/p services, partitions, and many interior finishes had already been installed. “We had to be more careful about deformation than we would for a typical building,” says Derrick Roorda, Buro Happold’s U.S. technical director.

Although the segments will probably stay put for several decades, they have been designed with circularity in mind. One day they could be decoupled and moved to another part of the airport, and possibly be converted to a different use, such as office space, points out Lomas. And, because the connections are bolted (except where the modules are tied to their foundations), the segments could even be easily disassembled and the steel members readily reused.

With all nine modules now in place, workers are building the concourse’s apron level, completing interior finishes, and installing the boarding bridges, among other tasks. Following a systems-commissioning process slated to start in March, the concourse will open in late 2025. According to Los Angeles World Airports, LAX’s owner and operator, the OCR approach shortened the construction timeline by six months and saved $30 million. Many of these economies can be attributed to avoiding the security screening required for building on an active airfield—and the associated time and expense. In a traditionally constructed airport project, “not only personnel, but every bolt needs to go through the TSA,” points out Roorda.

The team behind the expansion of Concourse D at ATL—the world’s busiest airport, with more than 100 million travelers in 2023 alone—is taking a slightly different tack, combining prefabrication with stick-built construction. The $1.4 billion project will widen the structure from 65 feet to 99 feet and extend its overall length by 288 feet. Ross Payton, aviation-sector leader at Corgan, says the revamped concourse will be more comfortable for travelers. It will have a taller interior volume, with 18-foot ceilings; larger hold rooms, with 20 percent more seating; roomier circulation spaces; more food options; and larger restrooms. When both north and south wings are complete, Concourse D will have 34 gates for next-generation aircraft.

The expansion is being implemented in phases, so that no more than eight gates are taken out of operation at any one time, a mandate from the client, explains Todd McClendon, senior vice president of aviation with WSP, the project’s program manager as part of a joint venture with H.J. Russell and Turner & Townsend. Starting with the north wing, contractors are building steel-framed, shoebox-like modules—some as large as 30 by 192 feet—in a nearby assembly yard and, as with the LAX project, moving them into place overnight with Mammoet’s SPMTs. The team will next rely on more conventional techniques to build over the existing two-story concourse, and, once the new enclosure is complete, demolish the original upper level from within.

As of September, the first five modules had been put in place, with six new gates already in use. The north wing is expected to be complete by the summer of 2027, and the entire concourse two years later. According to WSP’s initial estimates, the combination of off- and on-site construction will shave eight to 10 months off the project timeline compared to a more conventional approach. It will also keep a maximum number of gates in operation at any one time. “In terms of per-day gate revenue, it made total sense,” says McClendon.

Prefabrication or modular construction won’t be a good fit for every airport. But if the projects in Atlanta and Los Angeles deliver on their promises, we will be seeing many more relying on these strategies.

Source: Architectural Record

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!