MMC: Cutting the Red Tape and Navigating the Politics

Modular construction faces many challenges on the path to help solve the housing crisis, MiTek

Offsite construction has been featured more frequently in the national media spotlight for its potential to help bridge the gap in the country’s housing supply shortage.

It’s popularity can only grow. According to the Modular Building Institute, only 5.5% of buildings were built using modular in 2021, with modular defined as the use of factory-made and assembled panels, walls, or entire housing units, that are transported to a job site where the rest of the assembly takes place.

Now, modular is trending for its potential to meet the need for additional housing supply with its efficiencies and lower cost.

Samantha Hill is the founder and managing principal of development consulting firm Design With Skill where many of her clients are attracted to offsite and modular construction for its many benefits—the majority interested in potential cost savings in today’s pricy environment.

And, while the benefits are many, there are an equal amount of challenges that are intimidating roadblocks for offsite construction to reach broad adoption.

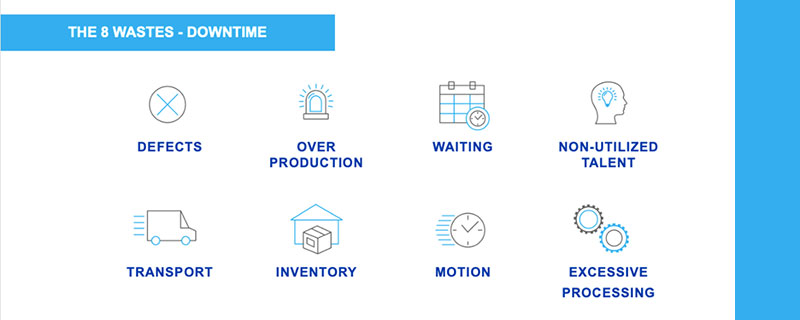

Mark Lee is the senior vice president of global home building solutions at construction technology company MiTek and outlines the eight wastes of manufacturing as defects, overproduction, waiting, non-utilized talent, transportation, inventory, motion and excessive processing.

The offsite manufacturing of housing is no different.

Removing Red Tape

First, offsite is stymied by bureaucratic limitations. As Hill has experienced in California, modular housing is regulated by a state agency, Housing and Community Development, that is responsible for processing and enforcing building permit approval of the modular housing components in a project, defined as “factory built housing.” The remaining onsite construction is regulated and enforced by another agency or authority based on the type of project.

“Unfortunately, this can be a very arduous and complicated process,” she said. “The management and navigation of this complex permitting system adds a significant amount of time, dedication, and often requires expertise from the design and development team, which adds costs to a project.”

She also has seen politics play a role in the development of modular construction policies, such as labor disputes like prevailing wage requirements, particularly when the modules are manufactured overseas.

“As with any heavily regulated industry, various agencies and regulatory bodies are often at odds with one another in an attempt to meet local versus state or regional needs,” Hill said. “Navigating these political challenges requires calculated strategies.”

In addition to these challenges, the modular permitting process can be extensive. Often a third party plan reviewer and an inspector will need to be hired for the modular scope. Since the onsite portion of modular is very different than conventional building, the inspectors need to bring a new level of expertise and experience so issues like fireproofing between units and structural tie downs are correct.

Labor Versus Productivity

“We don’t need more workers, we need to help the workers that exist to become more efficient and drive metrics,” Lee said as he presented at the recent Housing Innovation Alliance Summit. “It’s not about labor availability, it’s about labor productivity.”

Hill recognizes that there are some inherent overlaps when offsite goes to the job site that if avoided could streamline the process.

“Traditional onsite systems and utilities must connect,” she said. “For instance, fire sprinklers must be installed in the modular units in the factory, but must tie into the onsite circulation areas or other non-modular program areas.”

Since the overlap exists, project stakeholders have to be disciplined with clear communication of roles and responsibilities. Lee emphasizes that modular requires a new level of systems thinking that also demands collaborative innovation.

Nailing The Factory

Much of the success of modular hinges on building out the right systems, process, people and place for the offsite work, says Brent McPhail, offsite specialist and founder of Brave Structures.

“In site built, the product only needs to be within a half inch for a window installation, but if a machine is installing it, that machine needs to be accurately programmed for that tolerance,” he said. “We need to design product for manufacture and assembly.”

When set up, the factory has to have enough space for production lines, storage, and offices, while considering the concrete thickness of the building, hook height, service power, crane layout, product flow, and column spacing.

McPhail recommends hiring the right group of experts to have it all come together, including an electrical controls engineer, mechanical industrial engineer, production supervisor, quality analyst, process engineer, maintenance coordinator, and software specialist.

He enforces the concept of “Design for Manufacture and Assembly – Refine for Automation,” that focuses on refining product design for smooth and cost effective automation. On top of that, the design should be optimized for better processes and lower costs, the design should be simplified by using standardized parts, and potential risks should be analyzed and mitigated.

A difficult challenge for a new factory is allowing for flexibility, or designing production lines to be adaptable to various products and demand changes. Many times when a line is set up it needs to stay that way for a set amount of time to have a significant return on investment.

Space also should be optimized to minimize the movement and handling of material, plus to have the right storage for raw materials, for work in progress, and for finished product before it is moved to the job site. At all these stages of completion, the product needs to be protected from the elements, adding another challenge into the mix.

Cracking the Code

Building code was written for onsite, stick-built structures. Since modular projects have a different process, new codes need to be created and approved by local jurisdictions.

Tom Hardiman, executive director at the Modular Building Institute and the Modular Home Builders Association, shared a host of examples from working on modular projects. Some of the feedback he heard from local officials included, “Our one agency staff person found a typo on page 13 of your submittal so we flagged it as a deviation and have to send the entire set back to you for resubmittal. By mail.”

He also was slowed down by feedback such as “Once your plans are approved by our agency, you also have to submit them to three other agencies for review.”

Another jurisdiction told him, “We want you to build the home here locally, and preferably using union labor.”

On top of these types of challenges, regulators struggle to divide inspections between the work happening in the factory and what happens on the construction site.

Hill explains that fire code has not taken into account the redundancy of walls on modular units. Plus, if the fire barrier is installed onsite during unit installation, it’s difficult to apply, but if the unit is transported with the fireproofing, then there is risk of damage.

Code compliance of the modular units is often not applicable or compliant in all states. This means that modular manufacturers must either design to the most restrictive and often most expensive code requirements, or limit the market to specific areas.

The current administration is working to simplify and streamline inspections and regulatory requirements. It invested in a $41.4 million grant for a mass timber modular demonstration factory in Portland, Oregon.

Trucking It

One of the most critical components of a modular project is transportation. The costs to get completed units from a factory location to a job site can add up quickly, so its necessary to lay out a cost-effective route, and limit the service area.

Not only does the transportation cost a lot, but it also puts design constraints on the product with specific height and weight limits. More constraints come into play during delivery of the modular components when trucks need the space to unload and then a crane needs access to put the module in place.

Ignorance And Education

So many contractors and pros are in the twilight of their career, so know nothing other than working onsite. Out of habit or misunderstanding, a traditional builder can use the wrong construction standards, instantly increasing costs and destroying schedules.

These misunderstandings, or knowledge shortages, can easily lead to over budgeting, an unfortunate and common contingency for unknown and unfamiliar risks.

Fortunately or unfortunately, the marketplace for modular construction is growing, which is good for competition to drive innovation, but bad for the industry’s reputation if some aren’t set up to deliver.

Common Misconceptions

“Modular construction is not necessarily cheaper than traditional construction methods,” Hill said. “The value lies in the reduced construction schedule. In some cases, up to eight months can be saved by going modular. However, the full development and construction team needs to collaborate early and effectively to ensure the reduced schedule is achieved.”

The labor involved also shifts from the field to the factory, raising economic impact issues around local union involvement and job creation.

Insurance coverage is another challenge.

“Professional services firms have a lot of trouble getting appropriate insurance coverage to assist in the design of modular,” Hill said. “Most insurance companies see modular as a product and not a service, very similar to car manufacturing.”

On top of that, there are misunderstandings in the financing of modular projects. Tyler Pullen, senior technical advisor at Terner Housing Innovation Labs, says there are lenders who don’t understand the modular model, which slows down the process of translating traditional mortgages to cover modular projects. This becomes an even greater challenge because with a modular project’s shorter time frame and pre-built nature, it requires more up-front investment.

Different Design Parameters

“Despite the replication and repetitious nature of modular, design only becomes more vital to its evolution and success,” Patrick Sisson wrote in The State of Housing Design recently published by the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University. “Beyond the challenges of practicing architecture within these constraints, the overall design of delivery mechanisms—and systems that can be built to fit different lots and scenarios—creates an even greater and more complex task.”

Modular presents new challenges, such as fitting modules securely on a flatbed truck, and the need to make every major design decision in advance.

“Designers and projects that treat these constraints as advantages can find new ways to achieve replication and reliably cut costs,” Sisson added in the report. “Design can be a tool to unlock the potential of this process.”

Most modular projects are designed as whole units or a kit of parts, and each approach has unique advantages. Designing as a kit of parts requires additional onsite coordination, but is typically faster and easier to construct and transport. Whole units require less onsite coordination, but limit design flexibility and need more detailed offsite work.

Hill warns of a few design limitations for transportation to the site. Corridors and balconies often need to be constructed onsite, making installation more challenging. Plus, modular unit width has limitations, so if a larger space is need it may require two modular units to be joined together in the field, again adding costs. There also are more structural design limitations than traditional construction, such as reduced openings to meet shear and torsional requirements.

“Each modular company is unique in the design and elements they provide in their units,” she said. “Some offer the exterior envelope during installation. Some offer attached balconies. Some have local manufacturing facilities, while others have overseas manufacturing facilities. Overall, there is a lot of variation, unlike car manufacturing, which has been regulated for over 100 years, standardization of modular manufacturing is in its infancy.”

Despite the variability, modular production typically means higher quality and time savings. The Terner Center for Housing Innovation reported that modular can save between 10 and 30% of construction time. Sisson writes that these productivity gains could have exponential value as modular reaches economies of scale, such as more efficient factories, lower material costs, and more developed supply chains.

As modular is adopted on a broader scale, new factories that depend on a steady flow of projects also will have the opportunity to survive and thrive. It’s time to welcome the innovation.

By Jennifer Castenson

Source: Forbes

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!